Teaching the Armenian genocide: facing history, developing and informed compassionate citizenry

- Jan 9, 2019

- 6 min read

Alain Navarra-Navassartian

ARTICLE

By studying the historical development of the Armenian genocide and other example of genocide, students could make the connection between history and how history can be used as a tool to prevent atrocities. There was no word to accurately describe what the Turks were doing to the Armenians. In the Ottoman Empire, journalists, diplomats and other witnesses struggled to find language to convey the depth and the enormity of the anti Armenian measures: « horror », « barbarity », « massacres », « deportations », or « ravages ». But no word captured the scale of the violence.

The lessons address the following essential questions:

What happened to the Armenians in 1915? What primary source evidence do we have of the crimes against the Armenians?

What different steps did the Ottomans take to try to destroy the Armenian people?

What can responsible people do when confronted with powerful evidence of acts against humanity and civilization? How can history be used as tool to prevent future atrocities rather than abused as a tool to reinforce divisions among people?

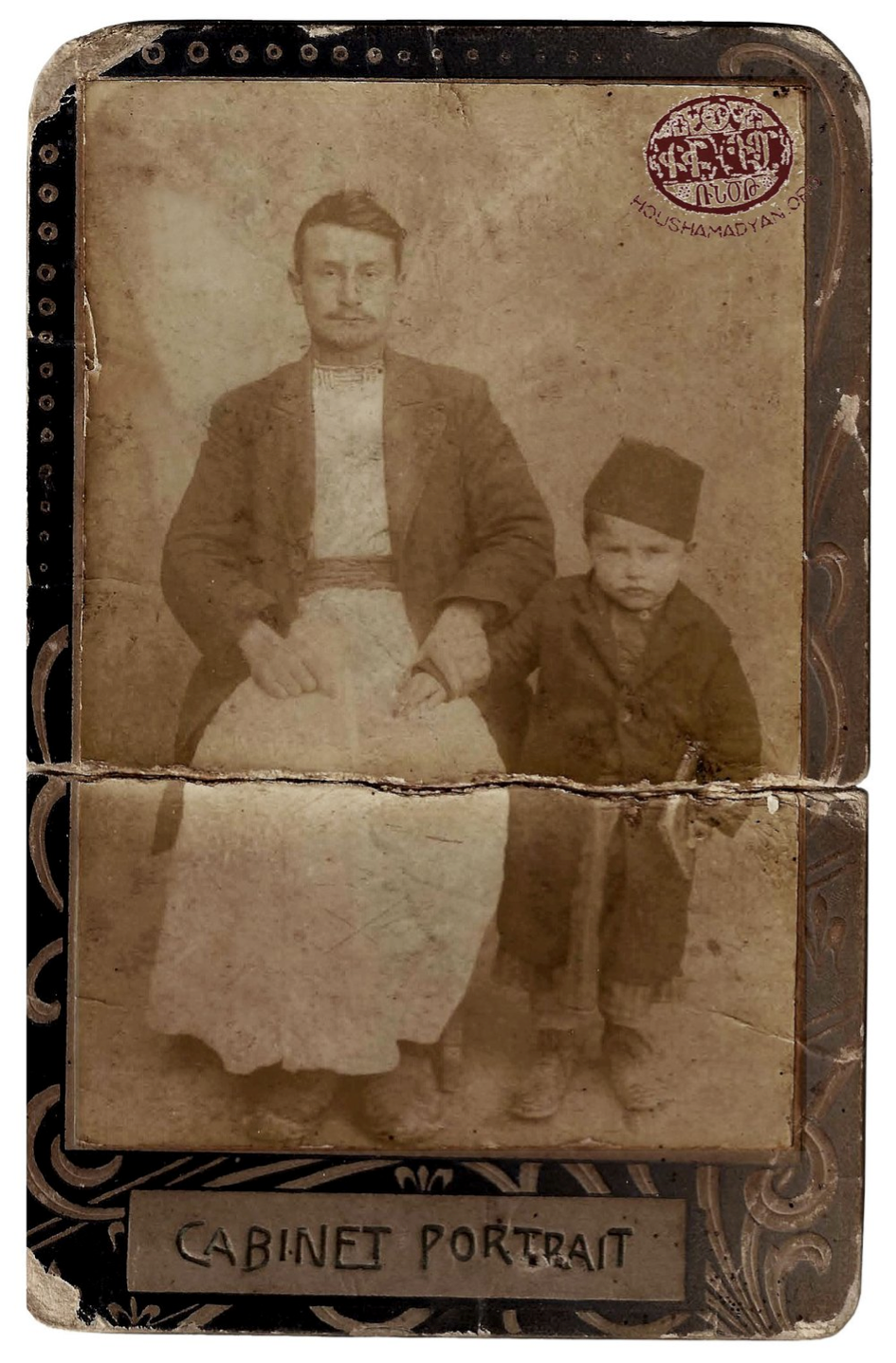

IDENTITY AND BELONGING

How identity is shaped by the past?

Why many Armenian refugees didn’t know their date of birth? Why some of them have changed their names?

How does your name connect to your family’s history?

Arschile Gorky’s real name was Vostanig Adoian.

THE ARMENIANS IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: WE AND THEY

The background information about the Armenian people will be explained.

In this lesson students will identify how religion, history, identity and national identity are used to create distinctives between we and they.

They will learn also, the challenges minorities faced when demanding equality in a traditional society through an examination of Armenian demands for civil rights in the Ottoman Empire.

During this period many European, American and Russian diplomats became concerned about the treatment of minority groups within the Ottoman Empire.

Their arguments and efforts to protect those minorities would set important precedent for the international movement for human rights.

The lesson addresses these essential questions:

Who are the Armenians?

What is the Ottoman Empire?

What rights did Armenians have in the Ottoman Empire?

What rights did the minorities have in the Ottoman Empire?

What challenges do minorities face when they demand more rights?

How are, religion, nationality and nationalism used to create distinctions between we and they?

ANALYZING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

In this lesson students will analyze primary source evidence of the genocide of the Armenians.

They will understand the systematic nature of the Armenian genocide.

They will evaluate how the study of history can be used as tool to prevent atrocities.

THE RANGE OF CHOICES

In this lesson students will examine primary and secondary sources to learn about the range of choices available to individual and groups in response to the Armenian genocide.

They will understand the dilemmas facing individuals, groups and nations responding to genocide in a time of war.

The lesson addresses these essential questions:

What did individuals, groups and nations do when they learned of the atrocities being committed against Armenians?

What choices did they make?

Who was in position to act in response to information about crimes being committed

What dilemmas do people face as they grapple with how to act in face of mass violence?

EUROPEAN RESPONSES TO THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

In this lesson students will analyze choices made by different European countries: France, England or Germany, for example, and their representatives during the Armenian genocide.

They will understand the concept of sovereignty and how it applies to these countries interventions during the Armenian genocide.

The lesson addresses these essential questions:

What options do governments officials have when they are aware of an injustice in another country?

Can we compare European response to the Armenian genocide to a current response to injustice? (Darfur for example)

What can we learn from the past to improve our response to injustice in the future?

French Armenian legion

IS THERE JUSTICE AFTER GENOCIDE?

In this lesson students will identify the results of the trials held by the Turkish government in 1919 and be able to describe what ultimately happened to the leaders of the Armenian genocide.

The lesson addresses these essential questions:

What is justice after genocide?

What is justice?

For there to be justice after crimes against the Armenians, what would need to happen?

Who should be held accountable? Who would need to be involved?

Soghomon Tehlirian’s trial session. Berlin.1921

DENIAL AND FREE SPEECH

In this lesson students will:

understand the definition of genocide.

evaluate historical evidence that supports the theory that the crimes against the Armenians satisfy the UN definition of genocide.

recognize the Turkish government’s interpretation of events and consider the implications of this denial for Armenians, Turks and others;

debate the limits of free speech as it relates to genocide denial.

The lesson addresses these essential questions:

Should all speech to protect? What about speech that attempts to distort history? Should people be allowed to deny the Armenian genocide ever took place?

What are the implications for Armenians, Turks and the international community of allowing denials of the Armenian genocide?

Why might Turkey want to deny that the Armenian genocide took place?

I am confident that the whole history of the human race contains no such horrible episode as this. The great massacres and persecutions of the past seem almost insignificant when compared with the sufferings of the Armenian race in 1915. The slaughter of the Albigenses in the early part of the thirteenth century has always been regarded as one of the most pitiful events in history. In these outbursts of fanaticism about 60,000 people were killed. In the massacre of St. Bartholomew about 30,000 human beings lost their lives. The Sicilian Vespers, which has always figured as one of the most fiendish outbursts of this kind, caused the destruction of 8,000. Volumes have been written about the Spanish Inquisition under Torquemada, yet in the eighteen years of his administration only a little more that 8,000 heretics were done to death. Perhaps the one event in history that most resembles the Armenian deportations was the expulsion of the Jews from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella. According to Prescott 160,000 were uprooted from their homes and scattered broadcast over Africa and Europe. Yet all these previous persecutions seem almost trivial when we compare them with the sufferings of the Armenians, in which at least 600,000 people were destroyed and perhaps as many as 1,000,000. And these earlier massacres when we compare them with the spirit that directed the Armenian atrocities, have one feature that we can almost describe as an excuse: they were the product of religious fanaticism and most of the men and women who instigated them sincerely believed that they were devoutly serving their Maker. Undoubtedly religious fanaticism was an impelling motive with the Turkish and Kurdish rabble who slew Armenians as a service to Allah, but the men who really conceived the crime had no such motive. Practically all of them were atheists, with no more respect for Mohammedanism than for Christianity, and with them the one motive was cold-blooded, calculating state policy.

Henry Morgenthau, Ambassador Morgenthau's Story (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co.: 1919), pp. 307-309, 321-323.

Bibliography:

Bruneteau Bernard. Le siècle des génocides. Armand Colin.2004

Lefebvre Barbara/Ferhadjian Sophie. Comprendre les génocides du XX siècle. Comparer-enseigner. Breal.2007

Chaumont Jean-Michel. La concurrence des victimes. Génocide-identité et reconnaissance.

La découverte.1997. (poche 2002)

Garapon Antoine. Des crimes qu’on ne peut ni punir ni pardonner. Pour une justice internationale.Odile Jacob.2002

Racine Jean-Baptiste. Génocide arménien-archéologie et permanence d’un crime.Dalloz 2006

Semelin Jacques. Purifier et détruire. Seuil. 2005

Vidal-Naquet Pierre. Les assassins de la mémoire. La découverte 2001

O’Siel Mark . Juger les crimes de masse. La mémoire collective et le droit. Seuil. 2006

Ternon Yves. Guerres et génocides au XX siècle. Odile Jacob. 2007

Kevorkian Raymond. Le génocide des Arméniens.Odile Jacob. 2006

Wievorka Annette. L’ère du témoin. Plon.1998 (poche 2002)

Apsel Joyce/Fein Helen. Teaching about genocide. ASA.2002

Bartov Omer. Mirrors of destruction, war, genocide and modern identity. Oxford press 2000

Bjornson /Jonassohn. Genocide and gross human rights violations in comparative perspectives.

Winter/Kennedy/Prost/Sivan. America and the Armenian genocide of 1915. Cambridge press.2004

Weitz Eric.D. A century of genocide : utopias of race and nation. Princeton university.2003

Chalk/ Jonassohn. The history and sociology of genocide. Yale university press. 1990

Alvarez Alex. Governments, citizens and genocide- a comparative and interdisciplinary approach. Indiana university.2001

Heidenrich John. How to prevent genocide. A guide for policy makers, scholars and the concerned citizens. Westport.2001

Bass Gary. Stay the hand of vengeance : the politics of war crimes tribunals. Princeton 2002

Schabas William. Genocide in international law : the crime of crime.

Adalian/Markusen/Jacobs/Totten. Chief editor Israel Charny. Encyclopedia of genocide. Santa Barbara.1999

Comments